More than four in ten adults in the United States live with obesity. The number keeps rising, and so do the linked problems of diabetes, heart disease, joint pain, sleep apnea, and some cancers. For decades the standard answers were “eat less and move more,” yet most people who lose weight this way gain it back within five years.

The body fights weight loss with powerful hormones that increase hunger and slow metabolism. New science now points to a different path. By copying the action of natural gut hormones, doctors can calm the brain’s hunger center, steady blood sugar, and help people lose fifteen to twenty percent of their body weight and keep it off.

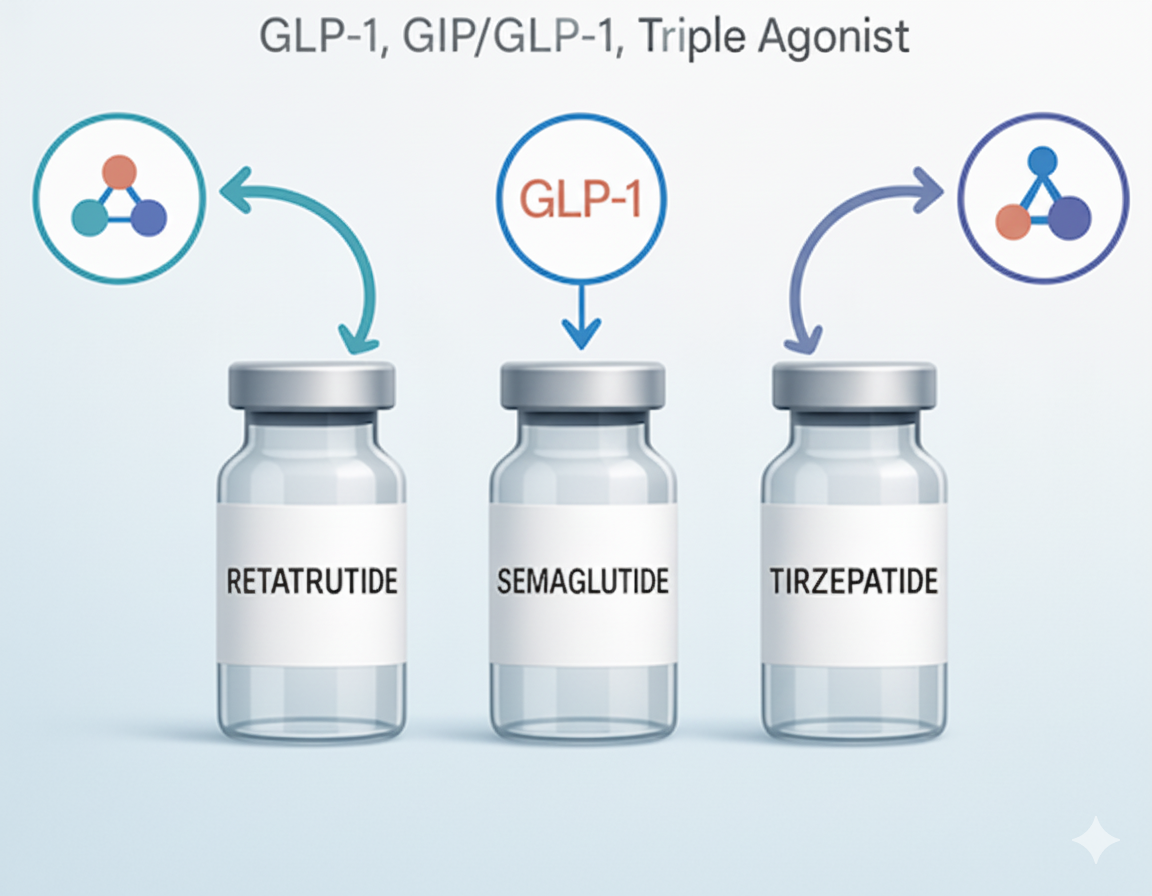

The two key hormones are GLP-1 and GIP. Drugs that act like them, including the well-known Adaptog Weight Loss Pens, are already changing how physicians treat obesity.

Why Old Diets Fail?

The human body treats weight loss as a threat. When fat cells shrink they release less leptin, a hormone that tells the brain “enough food.” Leptin drop triggers a cascade: the brain raises ghrelin (the “eat now” hormone), lowers peptide YY (the “I’m full” signal), and slows thyroid output so the body burns fewer calories.

These shifts start within days of cutting calories and last for years. The person feels relentless hunger, thinks about food more often, and feels cold and tired. Will power can push through for months, but biology usually wins.

Drugs that target only the brain, such as older appetite suppressants, raised blood pressure or mood problems and were pulled from the market. The breakthrough came when researchers looked lower in the chain, at the gut hormones released after meals.

These hormones tell the pancreas how much insulin to release, tell the stomach how fast to empty, and tell the brain when to stop eating. If you can boost the right signals, you can quiet the hunger drive without stimulants.

GLP-1: The First Gut Hormone in the Spotlight

GLP-1 stands for glucagon-like peptide-1. The small intestine releases it within minutes after you swallow food. It has three main jobs:

- It tells the pancreas to push out insulin only when glucose is high, so sugar levels do not spike.

- It blocks glucagon, a hormone that tells the liver to pump more sugar into the blood.

- It slows the pace at which the stomach empties, so you feel full sooner and stay full longer.

A fourth job was found later: GLP-1 receptors sit in the brain’s appetite center. When the hormone binds there, dopamine reward circuits calm down and the thought of food becomes less exciting. Early researchers tried giving natural GLP-1 by vein to volunteers.

Food intake dropped sharply, but the hormone lasts only two minutes in the blood stream before enzymes chew it up. Drug makers needed a way to make it last for a full day.

From Lizard Venom to Daily Shots

The Gila monster, a slow-moving desert lizard, eats only eight to ten large meals a year. Its saliva contains a protein called exendin-4 that looks and acts like human GLP-1 but resists the enzymes that break ours down.

Chemists copied the protein, swapped out a few amino acids so the immune system would not attack it, and created exenatide, the first GLP-1 drug. People with diabetes who injected it twice daily lost three to four pounds on average, a modest but real drop.

Next, scientists rebuilt the peptide chain to last even longer. They linked it to fatty acids that hitch to blood albumin, a large protein that circulates for days. That work produced once-daily liraglutide and later once-weekly semaglutide.

In large trials, semaglutide pushed average weight loss past fifteen percent, a number that once required surgery. The same molecule, sold under different brand names for diabetes and for obesity, proved that a gut hormone copy could deliver surgical-level results with a simple pen injector.

Adding GIP: The Second Hormone Enters the Mix

GIP stands for glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide. Like GLP-1, the intestine releases GIP after meals. It also boosts insulin and blunts glucagon, but it adds two new tricks: it pushes fat into fat cells and it may calm inflammation in metabolic tissues.

Early data suggested blocking GIP might help weight loss, but later work showed the opposite; activating GIP along with GLP-1 gives a stronger effect than either alone.

Drug makers built a single molecule that hits both receptors. The leading example, tirzepatide, links a GLP-1 backbone to GIP amino acid changes. In a head-to-head study, people taking the highest dose lost twenty one percent of body weight in seventy two weeks, beating semaglutide by another five percentage points.

Dual-hormone drugs are now called “incretin co-agonists,” but most people will simply think of them as the next generation pens after GLP-1-only versions such as Adaptog Weight Loss Pens.

How the Medicines Are Taken?

All current GLP-1 and GIP drugs are peptides, small proteins that stomach acid would destroy. They are given as subcutaneous shots, similar to insulin pens. The needle is thin, four millimeters long, and most users feel only a pinch.

Starter dose is low to limit nausea. The dose rises every four weeks until the patient reaches the maintenance level chosen by the doctor. People can inject at any time of day, with or without food. Pens come prefilled and do not require mixing.

An oral form of semaglutide exists, but it must be taken on an empty stomach with a small glass of water only, then the person must wait thirty minutes before eating or drinking or taking other pills.

Absorption is variable, and the shot still gives the best weight loss. Researchers are testing nasal sprays and skin patches, but these are likely two to three years away.

Typical Weight Loss Results in Trials

Trial data give the clearest picture because every calorie is logged, every step is counted, and placebos control for motivation. Key numbers:

- Semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly: average fourteen point nine percent weight loss after sixty eight weeks.

- Tirzepatide 15 mg weekly: average twenty point nine percent weight loss after seventy two weeks.

- Liraglutide 3 mg daily: average seven point four percent weight loss after fifty six weeks.

About one in four participants on semaglutide and one in three on tirzepatide lose twenty five percent or more, numbers that overlap with gastric sleeve surgery.

Importantly, weight loss continues for roughly sixty weeks before it levels off, which means the body finds a new set point rather than rebounding right away.

Real-world results are slightly lower because people skip doses or stop early, but twelve to eighteen percent remains common in clinic records.

Benefits Beyond the Scale

Trials measured waist size, blood pressure, cholesterol, liver fat, and sleep apnea scores. All improve, even before large weight loss shows up. The reasons:

- Lower blood sugar spikes reduce vascular stress.

- Slower stomach emptying cuts post-meal fat delivery to the liver.

- Brain receptor action lowers the urge to drink alcohol and often reduces cigarette craving.

A large heart-failure trial showed that semaglutide cut the risk of hospital admission by twenty eight percent in people with obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, a group that previously had no good drug options.

Kidney function also improves, and early signals suggest lower risk of dementia, though longer studies are underway.

Side Effects That Patients Notice

The most common issues are gut related. Between thirty and fifty percent of users report nausea, twenty to thirty percent have loose stools or constipation, and ten to fifteen percent notice heartburn.

These events are mild to moderate in most people, peak after each dose increase, and fade within two to four weeks. Eating smaller portions, skipping fried foods, and sipping water through the day helps.

Serious but rare events include gallstones, about one percent per year, and pancreatitis, roughly one in five hundred. Doctors screen for prior gallbladder disease and stop the drug if sharp stomach pain with vomiting occurs.

Rodent studies showed thyroid C-cell tumors at exposures many fold above human levels; human risk remains theoretical, but the drugs are avoided in people with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer.

Conclusion

GLP-1 and GIP drugs do not replace healthy habits; they make those habits easier to follow. For the first time, medicine offers a biologic tool that matches the power of surgery without cutting tissue.

The ripple effects already show up in grocery carts, restaurant portions, and even airplane seat-belt extenders. Analysts forecast that the obesity market will top one hundred billion dollars by twenty thirty, but the real gain will be measured in knee replacements avoided, heart attacks that never happen, and years of life lived free from weight-related disability.

Whether you hear about it from your doctor, the news, or a package labeled Adaptog Weight Loss Pens, the science is the same.

Copy the gut hormones, calm the brain, and let the body shed the extra fuel it has been forced to store. The future of obesity treatment is not another crash diet. It is a weekly pen that restores the signals evolution gave us, now made in a lab and shipped to your pharmacy.